Oracles In Quantum Algorithms

In April 7, 2020, thanks to a beautiful workshop held by Federico Mattei from IBM, I was introduced to the fundamentals of Quantum Computing, and it was love at first sight. I frantically studied the required maths, the Python language, the Qiskit library, and Jupyter notebooks. Then, after working hard on the basics for a dozen days, I was stuck with the most basic algorithm. But then I worked even harder, and finally I can say I got it: the problem was that I couldn't figure out why and how the so-called "oracles" should be implemented. Here is what I found.

We will start from the simplest scenario in which a problem can be solved faster by a quantum computer: Deutsch's algorithm. First we import everything we need to implement our oracle and the algorithm in Python:

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, Aer, execute

from qiskit.visualization import plot_histogram

from qiskit.quantum_info import Operator

Deutsch's algorithm is not particularly useful in practice, but it's a good initial step towards more complex quantum algorithms. Say we have a function which takes some zeroes and ones as input and returns 0 or 1 according to some logic:

We cannot inspect the function, but we can invoke it as a black box and, based on the output of our experiments, we are able to understand the underlying logic. We call such a function an "oracle".

An oracle with just one input will only be able to produce the following results:

If the oracle behaves like 1. or 2. it means that whatever input I use I will always obtain the same result: the function is then considered "constant" (always zero or always one). If instead it behaves like 3. or 4. it means that sometimes I get 0 and sometimes 1: the function could then be considered "variable", although in the more generic algorithm of Deutsch-Josza - which solves the same problem for inputs - we use the term "balanced" so we are going to use it here too (a balanced function gives 0 for half of the inputs and 1 for the other half, which by the way also applies in this case).

Although possibly confusing, we can call these functions for future reference like so:

- Zero: always gives 0 (constant)

- One: always gives 1 (constant)

- Identity: gives the unchanged input (balanced)

- Negation: gives the inverted input (balanced)

The Classical Way

In order to guess the logic a classical computer would need to call the function twice:

def guess(f):

constant = 0

balanced = 1

if f(0) == 0:

if f(1) == 0:

return constant # zero

elif f(1) == 1:

return balanced # identity

elif f(0) == 1:

if f(1) == 0:

return balanced # negation

elif f(1) == 1:

return constant # one

Let's test the four different functions:

def zero(bit):

return 0

def one(bit):

return 1

def identity(bit):

return bit

def negation(bit):

return 1 - bit

def test_guess(name, type):

print(name, 'is', 'constant' if guess(type) == 0 else 'balanced')

test_guess('Zero', zero)

test_guess('One', one)

test_guess('Identity', identity)

test_guess('Negation', negation)

Zero is constant

One is constant

Identity is balanced

Negation is balanced

Deutsch's algorithm instead guesses if the oracle is constant or balanced with just one call to , using the magic of quantum superposition. We will see how, but first we need to redefine the oracle in the quantum world.

The Oracle

We could think initially that the oracle could be implemented as a single-qubit gate, with just one input and one output:

input +--------+ output

|x⟩ ---| oracle |--- |f(x)⟩

+--------+

As this YouTube video shows, the matrices associated to the four operations we can do on a single qubit would be as follows:

- Zero (constant):

- One (constant):

- Identity (balanced): (equal to the Identity gate )

- Negation (balanced): (equal to the Pauli gate )

However these turn out to be useless, especially the first two since they are not even unitary.

As any gate in a quantum circuit, the oracle must be reversible (i.e. we can always determine which input generated the output we got). That's why we need to convert it into a two-qubits gate: the first qubit is the input value of the function, which isn't supposed to change as it passes through the oracle, and the second qubit is an output that usually starts with and will change into the result of the oracle:

input +--------+ input'

|x⟩ ---| |--- |x⟩

| oracle |

|0⟩ ---| |--- |f(x)⟩

output +--------+ output'

This could look strange at first for a software engineer, but its' nothing different from having an impure function which takes two inputs and returns two outputs, one of them being changed in the process:

def impure_function(x, y):

input_prime = input

output_prime = output.upper()

return {input_prime, output_prime}

print(impure_function('hello', 'world'))

{'hello', 'WORLD'}

However the oracle must be reversible always, even when output is equal to . So how do we deal with this?

If is also mapped to we will lose information when applyng the gate twice: what was the initial value of output? Not reversible. That's why we need to map to a different value, namely . So, to recap:

The outcome we expect from output' now looks like a XOR between output (the ) and output' (the ). That's why the generic form of an oracle maps output' with not just but with .

input +--------+ input'

|x⟩ ---| |--- |x⟩

| oracle |

|y⟩ ---| |--- |y ⊕ f(x)⟩

output +--------+ output'

Spoiler alert: when plugging the oracle in Deutsch's algorithm, we will use it in a "non-conventional" way: in fact, output will be initialized as and as a side effect input' will change!

So now we know that we need two qubits: the first one will be named input and the second one output.

qubits = 2

input = 0

output = 1

Defining The Four Operators

But how do we implement the four different oracles? The best approach I found for myself, which I'm going to explain here, is to find their unitary matrices by analyzing the expected output.

Zero

We know that whatever is the input, input' will remain the same and output will turn from to... well, . In bracket notation, where the least significant bit is input:

So the vectors and are mapped to themselves. This suggests the following matrix:

What about the last two rows? Let's remember that the oracle must be reversible, even with an output of (which will in fact be the case when using Deutsch's algorithm).

Knowing that the Zero function must give us when output is , we can now complete our output mapping:

So also the vectors and are mapped to themselves, which completes the matrix as an Identity (thank you Gabriele Agliardi for helping me on this!):

zero = Operator([

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1]

])

As we know, this operator corresponds to not doing anything at all inside the oracle:

input +------+ input'

|x⟩ ---| ---- |--- |x⟩

| |

|0⟩ ---| ---- |--- |0⟩

output +------+ output'

One

This oracle is pretty much the same as Zero, but this time we will get whatever the input was. Or, in bracket notation:

So now the vector is mapped to and is mapped to , which we can also describe as: "the first position becomes the third, and the second position becomes the fourth". This leads us immediately to the following matrix, without even the need to verify what happens when output is :

one = Operator([

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1],

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0]

])

This operator looks like a , which corresponds to just putting an gate on the output:

input +---------+ input'

|x⟩ ---| ------- |--- |x⟩

| |

|0⟩ ---| --|X|-- |--- |1⟩

output +---------+ output'

Identity

Contrary to the name, the resulting matrix will not be the Identity matrix. In fact:

So and (first position mapped to itself, second position mapped to fourth). This suggests the following matrix:

identity = Operator([

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0]

])

This operator looks like a CNOT on the output:

input +---------+ input'

|x⟩ ---| ---*--- |--- |x⟩

| | |

|0⟩ ---| --|X|-- |--- |0⟩ or |1⟩, depending on |x⟩

output +---------+ output'

Negation

Following the same approach, we can see that:

So and (first position mapped to third, second position mapped to itself). This suggests the following matrix:

negation = Operator([

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1]

])

This operator could be interpreted as a CNOT on the output, sandwiched by two 's on the input:

input +---------------+ input'

|x⟩ ---| --|X|-*-|X|-- |--- |x⟩

| | |

|0⟩ ---| -----|X|----- |--- |1⟩ or |0⟩, depending on |x⟩

output +---------------+ output'

Why is that? Well, if we look at the truth table:

We can see it as a CNOT with input as control and output as target, but:

output'is flipped wheninputis 0 instead of 1 so we need to negateinputbefore applying the CNOT; andinputmust be negated again afterwards to turn back to its original state asinput'.

It's easy to prove that gives that same exact matrix.

Or, as the aforementioned YouTube video shows, we can even see it as a CNOT with a subsequent negation on output, which makes even more sense in this simple case.

input +-------------+ input'

|x⟩ ---| ---*------- |--- |x⟩

| | |

|0⟩ ---| --|X|-|X|-- |--- |1⟩ or |0⟩, depending on |x⟩

output +-------------+ output'

So why bother with the sandwich? Well, for more generic cases, with multiple qubits in the input, the sandwich approach works every time as we can see in the documentation for the Deutsch-Josza algorithm.

Implementing The Oracles

We could now build the four different oracles as the circuits described above, or we can just define one function that makes use of the four unitary matrices that we already declared.

def oracle(type):

oracle = QuantumCircuit(qubits, name='oracle')

oracle.append(type, range(qubits))

return oracle

We can verify that the operators are well defined by invoking the following test function using all possible combinations.

def test_oracle_with(type, q1=0, q0=0):

circuit = QuantumCircuit(2, 1)

if (q0 == 1):

circuit.x(input)

if (q1 == 1):

circuit.x(output)

circuit.append(oracle(type), range(qubits))

circuit.measure(output, 0)

backend = Aer.get_backend('qasm_simulator')

return execute(circuit, backend, shots=1, memory=True).result().get_memory()[0]

def test_oracle(name, type):

print(

'{}(0):'.format(name), test_oracle_with(type, q0=0),

'\t',

'{}(1):'.format(name), test_oracle_with(type, q0=1)

)

test_oracle('Zero', zero)

test_oracle('One', one)

test_oracle('Identity', identity)

test_oracle('Negation', negation)

Zero(0): 0 Zero(1): 0

One(0): 1 One(1): 1

Identity(0): 0 Identity(1): 1

Negation(0): 1 Negation(1): 0

The Algorithm

Now that we know how to build oracles the tough part is over, and Deutsch's algorithm looks pretty straightforward in comparison. It just does the following:

- Negates the

outputqubit so it starts with - Applies Hadamard gates to both

inputandoutputto turn them into a superposition - Applies the oracle, whichever it is, in a "non-conventional" way (since from step 1 we set its to )

- Converts back the

input'with a Hadamard gate and measures it - The

input'qubit now seems to be changed in some cases, keeping the value if the hidden function was constant or turning into if it was balanced.

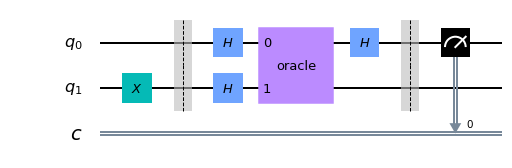

def deutsch(oracle):

cbits = 1

circuit = QuantumCircuit(qubits, cbits, name='deutsch')

circuit.x(output)

circuit.barrier()

circuit.h(input)

circuit.h(output)

circuit.append(oracle.to_instruction(), range(qubits))

circuit.h(input)

circuit.barrier()

circuit.measure(input, 0)

return circuit

circuit = deutsch(oracle(zero))

circuit.draw(output='mpl')

Let's give it a test.

def test_deutsch(name, type):

circuit = deutsch(oracle(type))

backend = Aer.get_backend('qasm_simulator')

guess = execute(circuit, backend, shots=1, memory=True).result().get_memory()[0]

print(name, 'is', 'constant' if guess == '0' else 'balanced')

test_deutsch('Zero', zero)

test_deutsch('One', one)

test_deutsch('Identity', identity)

test_deutsch('Negation', negation)

Zero is constant

One is constant

Identity is balanced

Negation is balanced

It works! But why? When an oracle features CNOT gates, wrapping it with Hadamard gates and starting with an output of triggers phase kickback, which flips the value of input instead of output. Only balanced oracles have CNOT gates, so only balanced oracles flip the input. So, in our case:

- Zero and One are implemented without CNOT gates: wrapping them in Hadamard gates does nothing to the

input, so it remains the same. It was before the algorithm, it's still after. The two oracles are then constant. - Identity and Negation have CNOT gates: wrapping them in Hadamard gates triggers phase kickback, so the

inputqubit flips from to . The two oracles are balanced.

What about the value of output'? Note that we don't measure it in the algorithm. The reason is that we don't care for the sake of the problem we are solving, and it holds the wrong result anyway. Say that we are testing the Zero oracle, but we start with an output of : output' will then be too, which is wrong because Zero should return . We could say that when using the algorithm the difference between Zero and One or Identity and Negation is lost in the X-basis, but the difference between constant and balanced is amplified.

We came up with the same results as the classical algorithm, but with just one call to the function . And now that we know everything we need about oracles we can better understand every other algorithm of the like, such as the more generic Deutsch-Josza for multiple inputs, the Bernstein-Vazirani which guesses the secret number in one shot, and Simon's algorithm which looks for two inputs that give the same output in sub-exponential time.

# IceOnFire